Many of us who peruse this blog love stories (whether those stories be told

in novels, playhouses or movie theatres.) Many of us here also seek to follow

the Apostle Paul’s encouragement to train our minds on “whatever is true,

whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely,

[and] whatever is admirable (Phil 4:8, NIV).” Often, we face a quandary. What

if, to tell a story honestly, unsavoury or downright evil behaviours must be

portrayed? Are we constrained—either as

consumers or creators of art—to keep certain topics or words off limits?

This spring, I found myself struggling through this question

with a group of college students in a class I was teaching on faith and the

arts. We could all agree upon extreme cases of exploitative and gratuitous sex,

violence and abusive language that are clearly outside the bounds of the

Philippians 4:8 mandate. But we were less sure what to do with greyer areas.

What if the questionable elements in a story are not there to titillate, but

rather because they are an important part of telling the truth about the human

condition? The Bible itself contains

many frank and unflinching depictions of human depravity; if we were to

legalistically and thoughtlessly apply the Philippians 4:8 mandate to

Scripture, we’d have to censor a good deal of what is there.

Despite several lively debates, we never did arrive at a

clear consensus on this issue. But we did settle on a framework that helped us

at least begin to more thoughtfully and prayerfully engage with stories of all

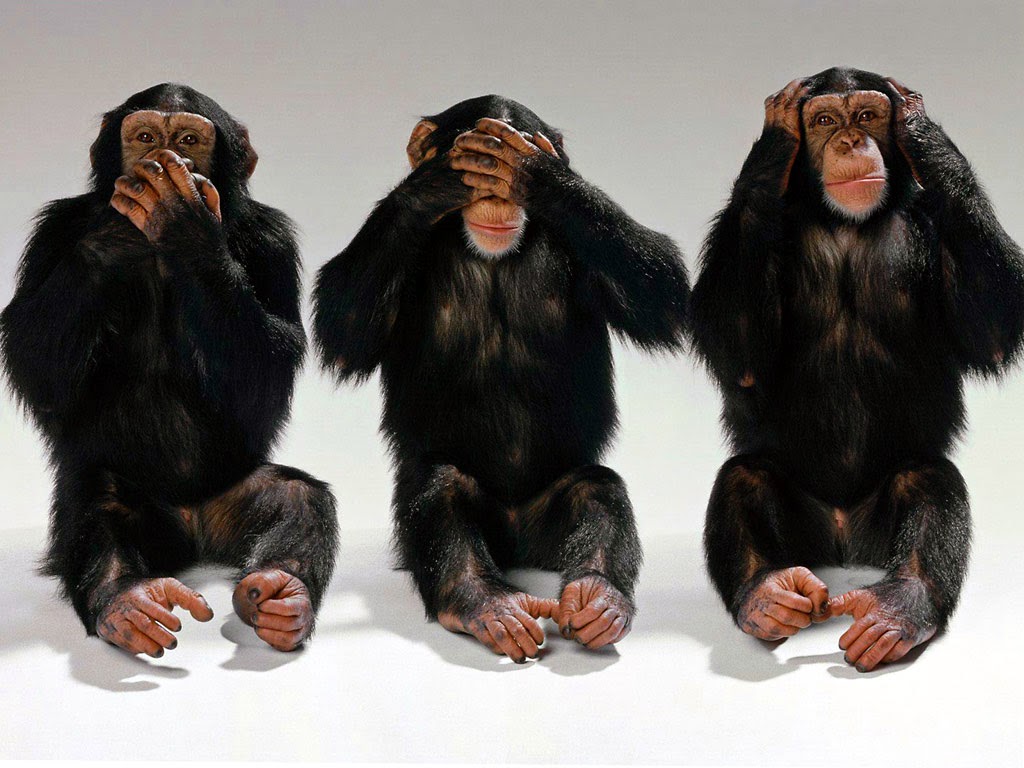

kinds. When tasked with evaluating a piece of art in any genre, we asked

ourselves three questions, inspired by the Church’s long history of

appropriating (quite appropriately, I think) Plato’s three Transcendentals.

Is it good?

Is it true?

Is it beautiful?

The first question – Is it good? – involves ethics and

morals. It requires us to consider not only whether a story contains offensive

words or scenes, but also whether the worldview it tacitly conveys is an

ethical one. It might be possible for a film to be rated “G,” but embody an

insidious worldview in which material success is considered the ultimate meaning

in life, or people are merely means to ends. Conversely, it might be possible

for a movie to contain violence, sex or language, but provide a perspective on

the human condition that moves the viewer towards a more ethical or moral

stance.

The second question – Is it true? – is an even more

theological one. Does the story—whether it is fact or fantasy or something in

between—say something honest about the world and the people who inhabit it?

Does it hint at anything true about God? Even if the worldview in a story is in

conflict with the Gospel, can it teach us something true about the perspectives

and needs of the people who hold it?

The third question – Is it beautiful? – has to do with

aesthetics. It asks whether the art in question is well-crafted and

successfully formed. A depraved story may be breathtakingly depicted. (In such

instances we should proceed with caution.) Or, as is sometimes the case in

explicitly “Christian” storytelling, a good and true story may be shabbily

crafted. (Caution is required here, too! Please!)

With these three questions, my students and I were able to

begin a process of discernment that each of us will be working through for the

rest of our lives. We might decide that a story lacking in one of the Transcendentals can still be worthy of our attention due to its strengths

in another. Most essentially, we felt

challenged to try to create work ourselves that was deeply good, unflinchingly

true, and as beautiful as we could possibly make it.

I pray you will go and do likewise!

Carolyn

PS – My own adventure in art-making this spring involves

recording an album of Christmas originals, which will be released October 15,

2014. This project will be my 11th CD; it’s the first one we’re crowdfunding. We’re asking people to consider

pre-ordering the album (with great discounts and perks) in order to help us

make it. Please check out our Kickstarter project. Thanks!